The global food system does the crucial work of producing and distributing food to a growing population but its hidden costs – caused by undernutrition, productivity loss and environmental damage – are currently estimated as equivalent to 10 per cent of global GDP annually, higher than the system’s contribution to economies.

In the most ambitious study of food system economics to date, leading economists and scientists from the Food System Economics Commission (FSEC) chart how the hidden costs of the global food system will continue to mount in the future unless we see major shifts in policy and practice. They show how transforming the global food system could instead present an opportunity of up to 10 trillion USD per year and how the costs of accessing this opportunity are relatively small compared to the potential benefits.

Opportunity to turn costs into contribution

FSEC – a joint initiative by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU), and EAT – has brought together leading experts on the economics of climate change, health, nutrition, agriculture and natural resources to develop a unique economic model. It provides the most comprehensive modelling of the impacts of two possible futures for the global food system to date: the Current Trends pathway and the Food System Transformation pathway.

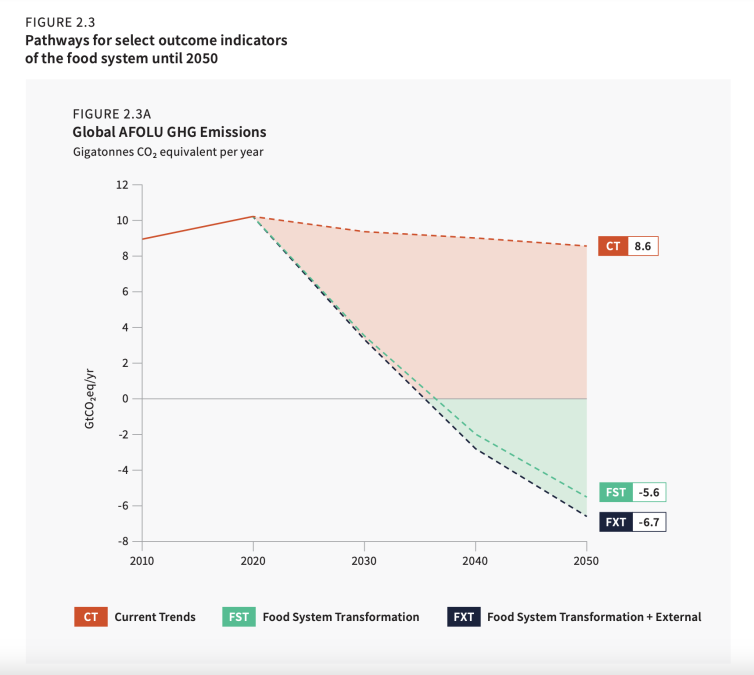

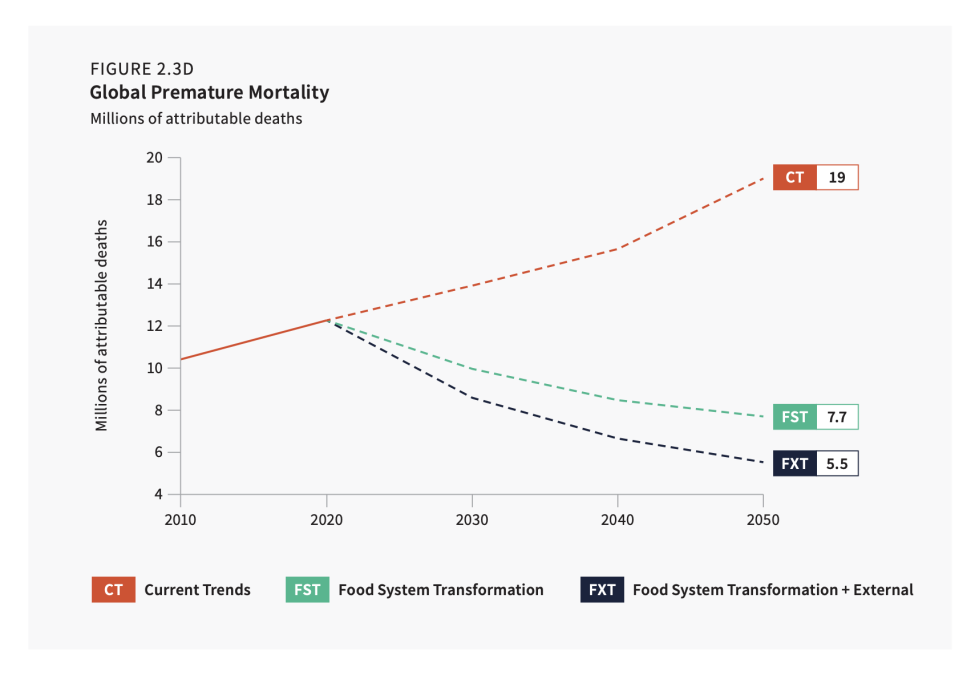

In the Current Trends pathway, by 2050 food insecurity will leave 640 million people (including 121 million children) underweight in some parts of the world, while obesity will increase by 70 per cent globally. Food systems will continue to drive a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, which will contribute to 2.7 degrees of warming by the end of the century compared to pre-industrial periods. Food production will become increasingly vulnerable to climate change, with the likelihood of extreme events dramatically increasing.

However, FSEC also finds that the food system can instead be a significant contributor to economies and drive solutions to health and climate challenges. In the Food System Transformation pathway, economists model that by 2050, better policies and practices could lead to undernutrition being eradicated and cumulatively 174 million lives saved from premature death due to diet-related chronic disease. Food systems could become net carbon sinks by 2040, helping to limit global warming to below 1.5 degrees by the end of the century, protecting an additional 1.4 billion hectares of land, almost halving nitrogen surplus from agriculture and reversing biodiversity loss. Furthermore, 400 million farm workers across the globe could enjoy a sufficient income.

FSEC also quantified the cost of achieving this transformation – estimated at the equivalent of 0.2-0.4 percent of global GDP per year – which is small relative to the multi-trillion dollar benefits it could bring.

Johan Rockström, Principal of FSEC and Director of PIK, said: “The costs of inaction to transform the broken food system will probably exceed the estimates in this assessment, given that the world continues to rapidly move along an extremely dangerous path whereby it is likely to not only breach the 1.5°C limit, but also face decades of overshoot, before potentially coming back to 1.5°C by the end of this century. Overshoot, even of 0.1-0.3 degrees, will add massive social costs across the world. Moreover, the only way to return back to 1.5°C is to phase out fossil-fuels, keep nature intact and transition food systems from source to sink of greenhouse gases. The global food system thereby holds the future of humanity on Earth in its hand.”

The current state of global food systems

These findings follow recent reporting from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which brought renewed attention to the hidden costs of current food systems – including unhealthy diets, undernourishment and environmental damage. FSEC’s Global Policy Report shows it is possible to bring these costs down through a combination of ambitious policies and incentives.

Policymakers need to face the food system challenge head-on and make the changes which will reap huge short- and long-term benefits globally.

Dr. Ottmar Edenhofer, Co-chair of FSEC and Director of PIK

However, many governments currently lack a coherent food system strategy and instead fund a fragmented and often contradictory set of incentives and regulations. Responsibility for food systems is often spread across many different government departments and existing incentives often work against health and nutritional outcomes, rather than toward them.

Dr. Ottmar Edenhofer, Co-chair of FSEC and Director of PIK said: “Rather than mortgaging our future and building up mounting costs that we will have to pay down the line, policymakers need to face the food system challenge head-on and make the changes which will reap huge short- and long-term benefits globally. This report should open up a much-needed conversation among key stakeholders about how we can access those benefits whilst leaving no one behind.”

The food system transformation pathway

The new FSEC Global Policy report outlines five broad areas of action – from technological innovation to policy incentives – to achieve food system transformation by 2050. It calls for the development of national food system transformation strategies while emphasising that challenges and solutions vary significantly from country to country.

These strategies should include:

- Policy incentives for the agriculture and food industry, taxing the production of the most damaging and unsustainable foods and directing the income to make healthy foods more affordable to low-income households. This could include, for example, taxing carbon and nitrogen pollution in food production.

- Realigning agriculture and food industry subsidies, supporting producers to shift their production toward healthy foods and sustainable practices. Many subsidies – such as un-targeted direct payments – currently work against health and environmental outcomes and could be reallocated.

- Encouraging healthier and more sustainable diets, tailored to local needs. There is no “one size fits all” approach, and solutions will include lowering consumptions of animal products in many parts of the world, while increasing access to it in others, to combat undernutrition.

- Investing in innovation to develop new agricultural technologies and widen the accessibility of existing ones to support small-scale farmers. The spread of technologies – such as remote-sensing – in-field sensors and market access apps can make farming radically more efficient and support producers while lowering emissions.

- Ensuring no one is left behind, by proactively mitigating potential knock-on impacts such as increases in food prices and job losses. These mitigations could include direct subsidies and support for both farmers and consumers and targeted investment in productive infrastructure, skills and access to finance for those most vulnerable, such as women farmers.

Gunhild Stordalen, Principal of FSEC and executive chair of EAT, said: “The food system has immense potential as preventative medicine for both people and planet, but is currently causing widespread damage. To avert this tragedy, global policymakers must revamp fragmented policies and regulations, utilising the food system’s power for positive change. FSEC offers an urgent economic rationale and provides political and economic decision-makers with the necessary evidence to transform food and land-use systems.”

This piece was initially published on EAT Forum and has been revised to suit Farming First’s editorial guidelines.