Tag: food

2021 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World

Global: World hunger and malnutrition levels increased last year, according to the recently published 2021 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report.

Read MoreMore Health-Giving, Life-Saving Vitamins and Minerals Through Modern Agricultural Techniques Applied To Food Staples

Global: The recent approval in the Philippines of Golden Rice, a variety enriched with pro-vitamin A, adds another long-awaited tool for treating vitamin A deficiency (VAD) in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs).

Read MoreQ&A with Dr. David Nabarro and Dr. Lawrence Haddad: Tackling world hunger by changing food systems

Global: We interview the winners of the 2018 World Food Prize at the Borlaug Dialogue in Des Moines.

Read MoreUnleashing Innovation For East Africa’s Millennial Farmers

Africa & Middle East: Awino Nyamolo from TechnoServe tells Farming First about how to harness the power of young people for Africa's food future.

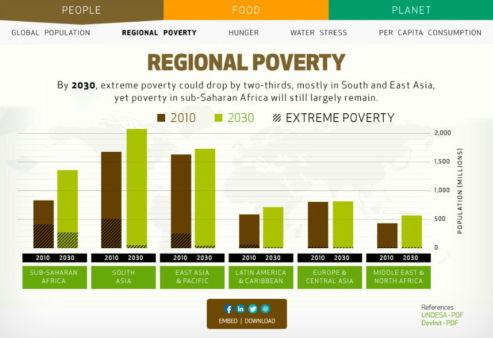

Read MoreFarming First Launches Infographic: Food and Farming in 2030

Global: This week in New York the first Open Working Groups will begin to discuss the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that will replace the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) when they expire in 2015. In an effort to inform the SDGs, Farming First has launched a creative infographic that skips forward in time to 2030, when the […]

Read More