Solutions to the world biggest problems are never straightforward. Hunger has been rising year-on-year for the last three years, Malnutrition, whether due to undernutrition or overconsumption is also on the rise.

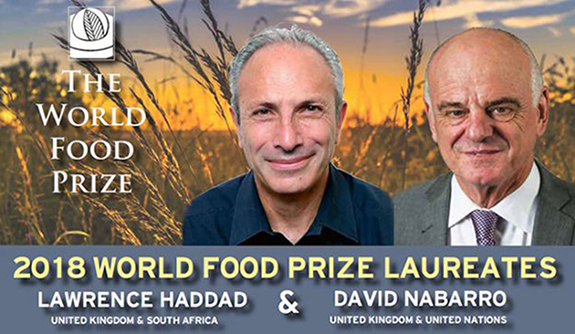

To discuss the way forward, ahead of World Food Prize week, Farming First caught up with Dr. Lawrence Haddad and Dr. David Nabarro, winners of the 2018 World Food Prize for their work on global maternal and child nutrition.

The Prize recognises the advancement of human development by improving the quality, quantity or availability of food.

Farming First: The FAO have recently announced that, for the third year running, world hunger is on the rise. Why, in your opinion, is progress stalling?

David Nabarro: “The last time we saw a big upswing in the projected number of hungry people in our world was between 2008-2009. That was when there was a worldwide spike in the prices of a number of staples, particularly rice and wheat.

This was associated with political unrest in more than 30 countries – the change of government in two – and evidence of a return to increasing rates of hunger and malnutrition in our world.

After that year, levels have been coming down quite dramatically so that we started moving towards just over half a billion and then the number has started to climb again. this is almost entirely the result of of unpredictable weather in large regions of the world and conflict. Sometimes countries are blighted by both.

Lawrence Haddad: “When adults experience hunger, it’s a highly painful and a highly distressing experience but they are much more able to bounce back. Very young children are unable to because it has disrupted their development.”

Farming First: Is there something that we have learned from previous instances that you have seen – that we can put to use to reverse this trend this time around?

David Nabarro: “Nutrition is particularly critical in the interval between conception and a child’s second birthday. If I had a magic wand, I would want to be sure that in conflict situations there is real attention given to women and young children in accessing nutrients in the form of nourishing food in the early periods of their lives.

These are people who are hard-to-reach.They tend to hide inside and protect small children. They’re also often having to provide nourishment for their small children out of sight of violence. Markets that they depend on tend to be sporadic or closed.

I want to see that women who are pregnant, women with very small children, and children are treated as special categories in war situations.

If they’re not given preferential treatment, the long-term consequences for the child will be very severe. There’s been a low level of collective consciousness about the damage done in pregnancy and early childhood as a result of insufficient attention to nutrition in war settings.”

Lawrence Haddad: “This upward trend is serious but it shouldn’t detract from the incredible progress we’ve made in reducing that number overall.

It’s worrying that it’s been going up in the last three years, but we think we know why that’s the case. These shocks – whether they are climate shocks or conflict shocks or weather shocks – are quite predictable in many ways.

We know where the risky areas are; we know roughly when these shocks are going to occur; we know roughly who they will affect. The divide between the development world and the humanitarian world is also creating barriers. It’s largely a western construct- the way we’ve set up the architecture.

Ethiopia is a very good example of how the humanitarian and development sector can better join together.

15 years ago the Ethiopian government told donors that while they welcomed food aid, it shouldn’t create longer-term resilience against future shocks. The Ethiopian government at the time set up the largest safety net and social protection programme in Africa, food aid is channelled into things that have improved the resilience and productivity of food systems in Ethiopia.

It’s been very successful. It has an assistance function, but it also has a protective, resilience function as well. It has forced humanitarian and development donors into the same stream of thinking”

Farming First: The link between poor food and nutrition security, and global security is being discussed more widely now. Hunger, peace and security will be one of the opening debates at the Borlaug Dialogue. What role can nutrition play in promoting more peaceful societies?

David Nabarro: “There is always the possibility that lack of access to food can prompt conflict. The anxiety about whether or not people can get the food and the water and the other attributes they need for life is all too often an underlying cause of violent conflict.

When countries come together and see themselves as collectively responsible this in turn reduces the likelihood that they will enter into violence as a means of resolving conflict.”

Lawrence Haddad: “Most conflict is driven by inequality, or at least a sense of inequality. Work by UNICEF and others shows that inequality in terms of malnutrition is actually rising faster within countries than it is between countries. So inequality within countries in terms of things like stunting and anaemia is either not improving or is actually worsening – and we know that inequality is a big driver of violence conflict.”

Farming First: What impact will failing to reach zero hunger have on the 16 other Sustainable Development Goals and particularly on economic growth?

David Nabarro: “Good nutrition is key to the realisation of all 17 goals. Although nutrition is slotted into goal two, it’s an issue that cuts right across the whole development agenda.

It almost goes without saying that people enjoying good nutrition are realising the whole sustainable development agenda. I don’t believe that the goals will be realised unless nutritional outcomes are good for everyone in all nations.”

Lawrence Haddad: “The thing that makes nutrition different is that it is multi-sectorally determined. What drives malnutrition is everything from governance, poverty education, water and sanitation, to the health system, agriculture and women’s empowerment.

When you explain it to policymakers you don’t express it in terms of improved nutrition alone, but in terms of better and improved work. David and I have spent a lot of our respective careers trying to help nutritionists make the case for why others outside of nutrition should invest in nutrition for their own benefit rather than just nutrition’s benefit.”

Farming First: Are there any examples of success you’ve had in making the argument for investing in nutrition?

David Nabarro: “We’ve seen it a lot actually. The term we usually use is ‘why not make your employment setting more nutrition-sensitive?’ What we’re really saying is whether it’s possible to drive good nutrition in the workplace.

For example, can you enable women to have nutritious snacks when they’re busy hard at work making garments that or offering a facility for women who are lactating to be able to breastfeed or provide milk on site?

A focus on good nutrition often increases the productivity and the sense of wellbeing of the workers in a plant or in a garment factor or agricultural plantation.”

Lawrence Haddad: “Both of us are essentially connectors. We connect issues and people and organisations. One thing that we are good at is connecting nutrition with wider issues. We could connect climate very easily in terms of what decisions people make on what to grow and what to eat have fundamental consequences for greenhouse gas emissions.

If you’re interested in the youth bulge happening in many African countries, policy makers can make the most of the demographic dividend that’s coming through investing in good nutrition. Same with universal healthcare. To make it financially and fiscally feasible, you have to ask the question: what’s the biggest driver of poor health today? It’s poor diets and poor nutrition.

To make universal healthcare financially feasible, you need to invest in improved diets to lessen the disease burden of non communicable diseases before they’re more prevalent.

There’s lots of different ways of connecting nutrition to other things that policy makers care about. Policymakers have lots and lots of things to worry about and it’s the people who shout the loudest and the most persistently that usually get their attention.”

Farming First: How can we combat the rise in non-communicable diseases through striving to making nutritious and safe food more available, affordable and desirable for all — especially for the most vulnerable?

David Nabarro: “There’s remarkably little collective understanding that food systems are just not right and they’re not right in a very large number of places. The challenge is that food systems remain primarily local and there’s no top-down solution that’s going to work.

I’ve been trying to work with different groups to think about what might be a possible approach to encouraging the transformation of food systems so that they are nutritious and sustainable all over the world.

We need to shift from seeing food as a form of to seeing food as nourishment which provides the basic ingredients on which our bodies develop all their different capabilities.

How do we make sure that our food systems yield the kind of food that is needed for good nutrition? Secondly, how can we make sure our food systems will restore ecosystems on which we all depend – particularly soil, water, sea and oceans, forests and biodiversity? Thirdly, how can we be sure that our food systems are compatible with climate change and actually do all they can to absorb and sequester carbon that otherwise makes temperatures rise? And lastly, how do we ensure that our food systems contribute to decent livelihoods and wellbeing for all the people who work within them?

Those of us in the know realise that the people who work in food systems – if we look at them across the world – tend to be some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in our world. They’re particularly vulnerable to adverse weather patterns so we need to help them to be both prosperous with decent livelihoods and resilience in the face of stress.

Unless all of us are looking at that, we’ll find it very hard to make the transformation that is necessary in line with the SDGs.”

Farming First: Do you have any final thoughts to share?

Lawrence Haddad: “If we want to transform food systems we have to transform ourselves and our relationship with food and nutrition. That’s all very important but there’s one hard, tangible fact that we’re all grappling with and one we should be really focusing our mind and that is how we get the price of nutritious food down. if we don’t get the price of nutritious food down, it will thwart all of the other goals.

While the price is going up, the price of food staples is going doing or is static There are lots of reasons why that’s happening and that’s a very tangible way of focusing all of our efforts.”