More than one third of the food that the world produces never gets eaten. From farm to fork, 1.3 billion tons of food waste are generated across the supply chain annually—on farms, ports, processing and manufacturing facilities, retailers, restaurants and homes.

Not only is the scale of food loss and waste (FLW) unfathomable as many as 735 million people around the world face hunger, but FLW accounts for 8 to 10 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions—approximately four times the emissions from the global aviation industry.

Reducing FLW and its associated emissions is critical to getting the world back on track with climate goals established by the Paris Agreement and preventing global warming past 1.5 °C.

How do food loss and waste contribute to methane emissions?

Much of the greenhouse gas emissions from FLW are emitted in landfills where food cannot properly decompose.

Inside landfills, food slowly breaks down and releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas that has 86 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide (over a 20 year period)—meaning that methane makes the climate warm faster.

To make matters worse, methane concentrations in the atmosphere have been growing rapidly in recent years. That’s why reducing methane is one of the most impactful ways to reverse climate change in the short term.

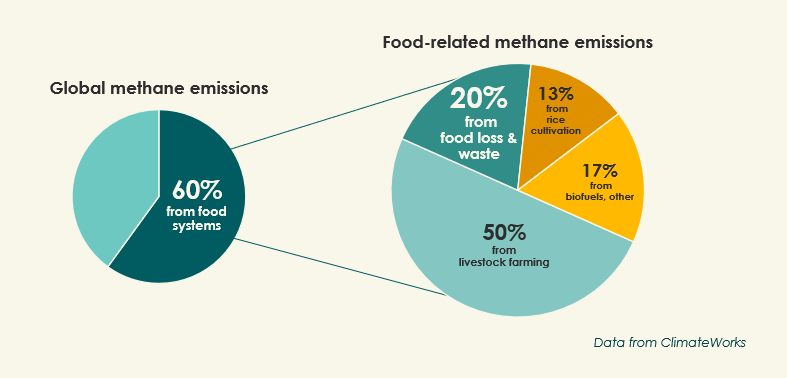

According to the ClimateWorks Foundation, food systems account for about 60 per cent of global methane emissions and FLW-related emissions account for 20 per cent of that. While this percentage may be lesser than emissions from other parts of the food system, reducing food loss and waste is nonetheless a critical climate strategy that can be acted upon immediately and has a substantial impact.

An opportunity to take action on methane from food waste at COP28

Addressing methane emissions needs to be prioritised at COP28, the 2023 United Nations climate conference taking place from 30 November to 12 December.

At this year’s COP, there will be a “global stocktake,” an assessment of the climate progress made since the Paris Agreement was signed by nearly 200 countries in 2015. Limited progress has been made in the areas of FLW reduction and that’s why we’re calling for the following actions to be taken at COP28:

- All countries must integrate FLW into both short- and long-term Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) or national climate plans with specific actions, targets and indicators. Today, only 21 countries currently mention food loss and waste in their NDCs, and more than half of countries with national climate plans have failed to include measures to cut methane emissions from organic waste.

- Both the private and public sector must invest to rapidly transform food systems and scale innovations to reduce food loss and waste. Currently, only three per cent of global climate finance is being invested in food systems, according to the Global Alliance for the Future of Food.

- Countries should implement food banking as an intervention to address food waste, methane emissions, and hunger. Food banking already exists around the world across regional food systems and contexts.

How food banks are reducing methane emissions

The Global FoodBanking Network (GFN) is doing its part to close gaps in tracking and data around the methane emissions prevented via food recovery by food banks around the world.

Last November, GFN received significant investment by the Global Methane Hub, who are funding an pilot project to develop a methodology to quantify methane mitigations. Once a robust and credible methodology is in place, food banks and other organizations that recover and redistribute surplus food can prove the efficacy of their actions to mitigate methane.

GFN can then assess the scale of food banking’s efforts to reduce methane worldwide and share this information with governments and private sector actors to ensure greater investment for food banking and inclusion in climate action strategies.

Addressing food loss and waste is not only crucial for mitigating methane emissions but also for achieving broader sustainability goals outlined in the Paris Agreement. By reducing food waste through innovative technologies and interventions, improved supply chain management or global climate cooperation, the world can simultaneously curb methane and other greenhouse gas emissions, conserve resources and promote a more sustainable and resilient food system.

With COP28 already here and the levels of FLW still far too high, there’s no time to waste.