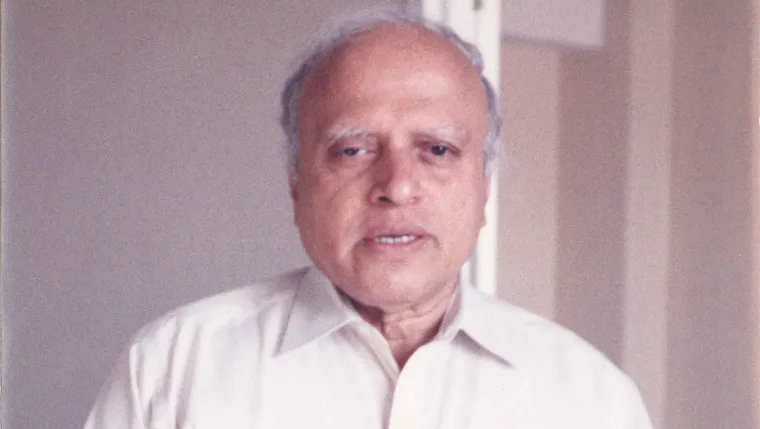

We were a couple of Indians at the Bombay Club—not in our native land, but about a block from the White House, at a restaurant in Washington, D.C. My companion was a soft-spoken global icon. I was a young man in search of a mentor. This was our first encounter.

We won’t meet again: M.S. Swaminathan died on the 28th of September at the age of 98. He leaves behind a fantastic legacy as a brilliant agricultural scientist, an author of the Green Revolution, and the saviour of Indian agriculture.

He was also my hero and mentor—and it says a lot about Swaminathan that he was willing to visit with me in 1997 when I was embarking on my career as a geneticist who seeks to help the world grow more food.

I wouldn’t have blamed him for declining my invitation to get together because he had better things to do. Except for his friend Dr. Norman Borlaug, he was probably the most critical crop geneticist of the 20th century. When the World Food Prize gave away its inaugural award in 1987, it honoured Swaminathan as its first laureate.

Hundreds of millions of people may be alive today because of his work.

As a young man, Swaminathan watched India struggle to feed its people. In the 1940s, a famine ended millions of lives. Witnessing the disaster persuaded Swaminathan to abandon his goal of a career in medicine and instead devote himself to food production in a nation whose survival required massive amounts of imports.

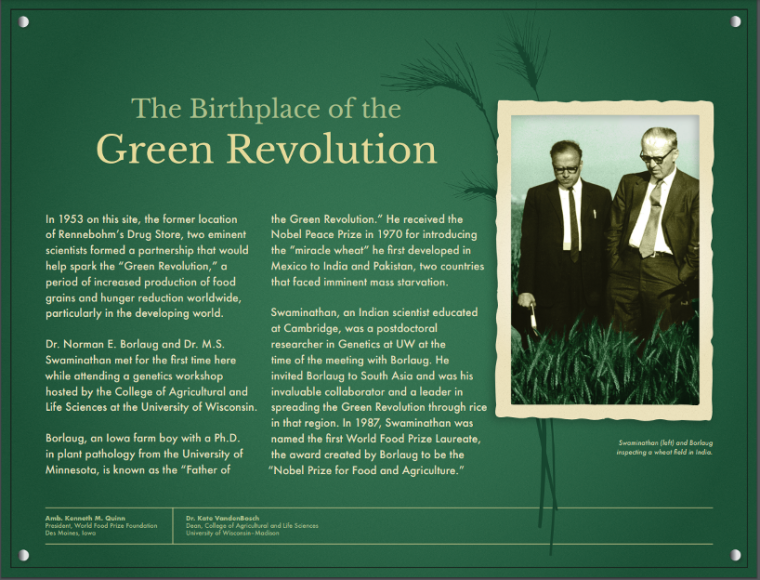

To pursue an advanced education, he went to the Wageningen Agricultural University in the Netherlands, then to the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, and finally to the University of Wisconsin in the United States. That’s where he met Borlaug in 1953, during a genetics conference in Madison.

Their first meeting occurred at a drug store, on a site that the University of Wisconsin now marks with a plaque called “The Birthplace of the Green Revolution.”

Thus began one of the most essential scientific collaborations in history.

Borlaug was already conducting research that was starting to boost crop production worldwide. He had worked mainly in Mexico and Pakistan, but he wanted to take his ideas to the farmers of India, a place that desperately needed his innovations.

Swaminathan aspired to get him there, and it took nearly a decade of petitioning government officials to make it happen. Borlaug finally arrived in 1963, and the two men began to develop the crop varieties that transformed India’s agriculture.

In 1966, India imported 18,000 wheat seeds from Mexico—and the farmers who planted them saw their yields triple. By the 1970s, Indians grew enough wheat and rice to supply domestic markets. By the 1980s, India was exporting food.

Because of Borlaug and Swaminathan, India went from being a hungry nation to a food superpower.

Today, India is one of the planet’s top producers of wheat, rice, fruits, vegetables, eggs, meat, and more. It continues to face food-security challenges, but the threat of catastrophe that once loomed is forever gone.

As a student in India, I knew our debt to Swaminathan. By the time I had become a young professor in the United States, I had the courage to email him. Would he like to meet? He replied quickly and graciously, leading us to the Bombay Club, where we sat and talked for three hours.

In the years since, we saw more of each other and traded countless messages. He was consistently polite in his manner and generous with his insights.

My career advanced—not to anything like the heights of Swaminathan, but to the point where I gained a public profile as a crop scientist who has called for India and other developing countries to embrace the promise of biotechnology in food production.

Swaminathan joined me in advocating for Bt cotton, which is now overwhelmingly preferred by Indian farmers for its ability to defeat pests and improve yields. I’m sad that he was less encouraging of GM brinjal (also known as eggplant). This remains an essential technology for India’s future.

Yet this reluctance does not detract from his accomplishment. Without him, we wouldn’t even be able to think about the possibility of GM crops.

India and the world are better because Swaminathan gave us the Green Revolution. Our job as his inheritors in the 21st century is to make it an Evergreen Revolution.

This originally appeared on the Global Farmer Network blog.