In rural Sub-Saharan Africa, a woman smallholder farmer is faced with tradeoffs every day. She’s responsible for paying her children’s school costs that increase each year. She grows staple crops, but drought and fluctuating weather patterns have wreaked havoc on production. She has no land rights and mostly likely no credit. Meanwhile, every day more people seek safety in her community as they flee violence in neighbouring countries. Should she send her kids to school or have them help out at home? Should she share her limited food reserves with refugees? Should she cut down more of their orchards to cultivate a larger area?

This is a common scenario faced by countless farmers in Uganda, Nigeria or DRC and other countries. These dilemmas are the same as those faced by the global community as it figures out how to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG #2 around ending hunger. Ending hunger—more so than any other SDG—demands a holistic understanding of the complex systems and linkages across food security, urban growth, gender equality, poverty, conflict and natural resources. How do decisions to increase production affect water resources? Are increases in income prompting male farmers to co-opt traditionally female-led work? Are current interventions going to be obsolete when the next inevitable conflict or a natural disaster completely wipes out farmlands?

We cannot simply double agricultural production and be satisfied that a target was met. We have to consider the tradeoffs. “Sustainable” requires us to think big and long-term. And this may seem daunting, but we have important tools at our disposal that can help us realize the ambitious goal of ending hunger, achieving food security, improving nutrition and promoting sustainable agriculture.

One critical tool is satellite imagery. The next revolution for agriculture will be multispectral—a revolution in blue, green, red, near infrared and short-wave infrared. Satellite imagery can help evaluate tradeoffs across the food production spectrum, whether that be the value chain, the continent or the sector, as well as the nexus of food security, poverty and environmental sustainability. Imagery provides invaluable insights specific to agriculture (think crop yields, crop health), but also about the context of the agricultural system (think enabling environments like road networks, reducing risk for credit). Imagery is also an authoritative information source that provides an incredible return on investment when you leverage all it has to offer. Governments need to take advantage of that, and we need to better communicate that ROI—whether it’s faster access to information, saving costs on surveys, or de-risking private sector investment.

Imagery can address these information gaps while also rallying disparate stakeholders around a common operating picture. What other information source provides value to everyone from scientists to humanitarians to policymakers to extension workers to farmers themselves?

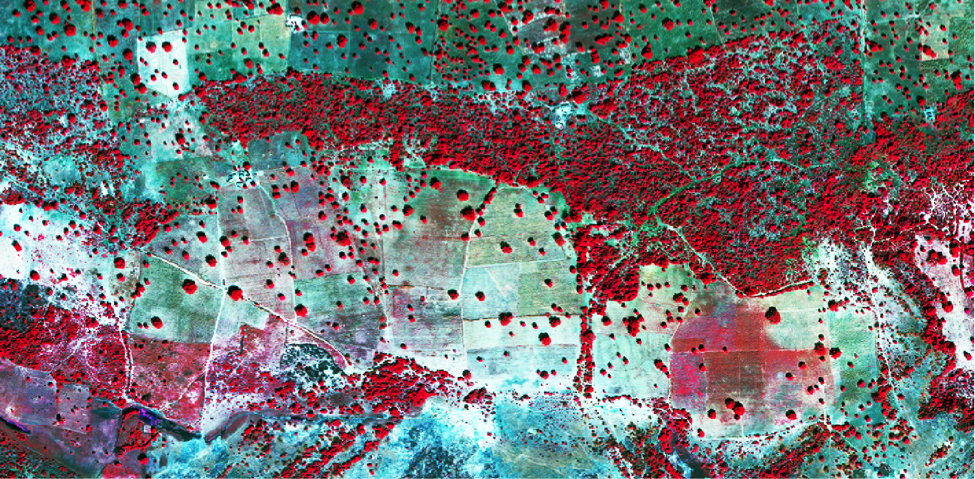

Leveraging imagery is an important tool in the food security toolkit. ICRISAT used DigitalGlobe’s high resolution imagery in Mali to evidence adoption of good agricultural practices. Analyzing crop health at the plot level provides an important insight as to whether or not those farmers were applying the recommended amounts of fertilizer. As you can tell from the image below where red indicates healthy vegetation, the thriving sorghum are those that received the appropriate amount of NPK.

False colour, high-resolution imagery over smallholder fields in Mali. Imagery from DigitalGlobe.

Imagery from Digital Globe, Analysis from ICRISAT

The image to the left shows the crop health of sorghum plots with varying levels of fertilizer applied. Red indicates healthy crops. In this example, F has received the recommended fertilizer amount with A, as the control, receiving none.

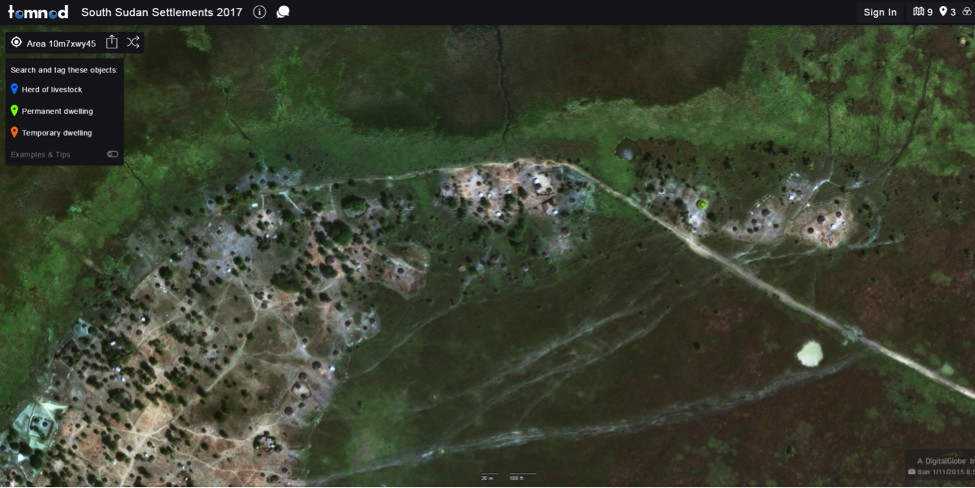

Another example would be gathering information at the nexus of conflict, population migration and food security. Working with the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET), DigitalGlobe is identifying permanent settlements, temporary settlements and herds of cattle in South Sudan so the international community can better assess the food security status in the region and make data-driven plans to intervene.

Using the Tomnod crowdsourcing platform, thousands of volunteers across the world are tagging settlements and herds of cattle in South Sudan to support the Famine Early Warning System Network.

Want to join the multispectral revolution? Click here to help us map migration in South Sudan to avert a famine.

Featured image photo credit: Trocaire – Lona Kiji who fled her home in South Sudan photographed outside her tent in Bidi Bidi refugee camp.