Tag: rural women

How the Climate Crisis Affects Rural Women: A Conversation with Lauren Phillips

Global: Lauren Phillips, FAO’s Rural Transformation and Gender Equality Division, explains how the climate crisis impact women differently than men.

Read MoreRural Women Play a Transformative Role in Food Systems

Africa & Middle East: Transforming Africa's food systems relies on empowering rural women, responsible for producing staple foods, with the same resources as men.

Read MoreCultivating Resilience: Uniting against Climate Change for Africa’s Food Future

Africa & Middle East: Building resilience in food systems means increased attention, compassion and united action across Africa.

Read MoreBuilding the Resilience of Smallholder Women Farmers in India

Asia: Empowering smallholder women farmers in India in agriculture.

Read MoreYoung, Rural, and Female: Why Agriculture Needs Girls

Global: Investing in rural girls is critical for solving global hunger.

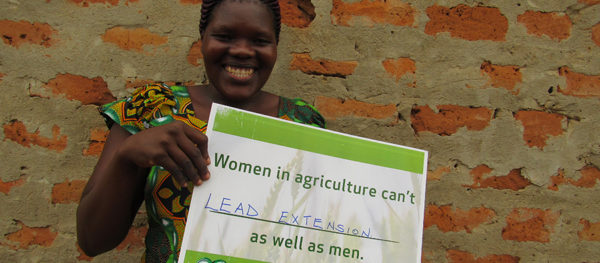

Read More#FillTheGap! Breadwinners and homemakers in Malawi

Africa & Middle East: Malidadi Chilongo learned to diversify her farm and invest in livestock, improving her family’s diet and investing in a back-up to sell if her crops fail because of extreme weather.

Read More#FillTheGap! Women bring home the bacon in Malawi

Africa & Middle East: By practising conservation farming techniques, Ethel Khundi produced almost three times more maize than she had done a year earlier, offsetting livestock losses to swine flu.

Read More#FillTheGap! Women in Burkina Faso warrant greater credit

Africa & Middle East: Fatima Nadinga was among those who had been typically blocked from crucial credit until a USAID-funded project implemented by non-profit CNFA trained women in the “warrantage” credit mechanism.

Read More#FillTheGap! Scaling up equality in Kenya

Africa & Middle East: With the help of IFDC, Beatrice Gichuru is setting the standard for equality in her area by proving that a woman can truly succeed with or without a husband.

Read More#FillTheGap! Empowering female agripreneurs in Zimbabwe

Africa & Middle East: Ruramiso Mashumba defied expectations by quickly growing her farming business in Zimbabwe, where women often work unpaid in agriculture.

Read More#FillTheGap! Equal rights are brewing in Colombia

Latin America & the Caribbean: Cocoa growers' leader Lidia Grueso has overcome gender bias to become a union manager, and is now leading the charge to improve access to credit for all cocoa farmers, including women.

Read More#FillTheGap! Sowing the seeds of equal access to resources in Uganda

Africa & Middle East: Nancy Adong was recruited as a community-based trainer in Northern Uganda and took charge of two farmer groups, winning her newfound confidence, leadership skills and respect.

Read More