Tag: COP22

Lawrence Biyika Songa: The Cost of Climate Change for Ugandan Farmers

Africa & Middle East: Uganda’s representative to the United Nations climate talks outlines the steps he recommends for successful adaptation to climate change

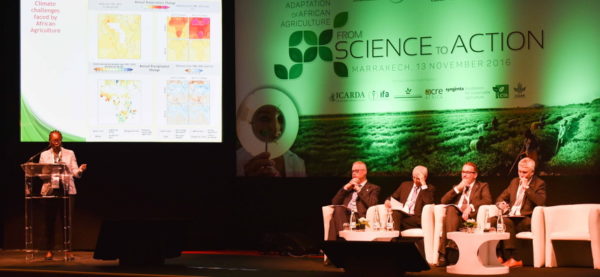

Read MoreAdaptation of African Agriculture (AAA) Gains Momentum at COP22

Global: As global talks on including agriculture in climate negotiations stall, the Moroccan AAA initiative offers hope on a regional level.

Read MoreWhat Does the Paris Agreement Mean for Food & Agriculture?

Global: As COP22 in Marrakech gets under way, CCAFS Director explores the implications for the food system now the Paris Agreement has entered into force.

Read More