Alessandro Caprini, Junior Consultant at the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, takes stock on how countries’ various climate plans will transform their agriculture, food and land use systems – a synopsis of a recent report by the Food and Land Use Coalition which he co-authored.

Agriculture, food, and land use systems lie at the heart of key climate and sustainability challenges. They are responsible for a significant share of carbon emissions, but trees and soils are also sinks that take up carbon from the atmosphere, making them central to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

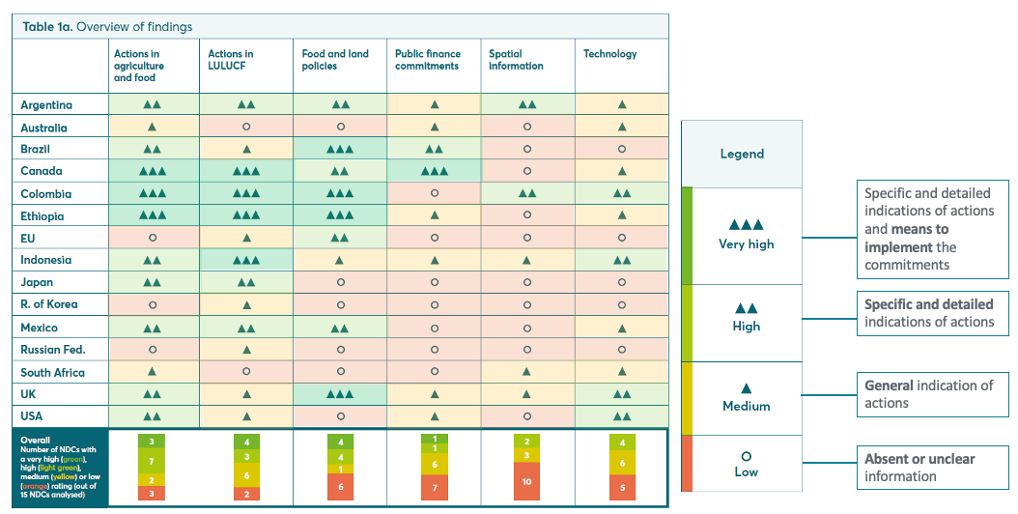

A recent brief by the FELD Action Tracker and published by the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU) analysed a set of 15 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – or national plans designed to outline how countries intend to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement. These NDCs were submitted by G20 and other countries ahead of COP26 to assess how countries’ climate plans address and outline key transitions in agriculture, food and land use systems.

Countries pledge action, but concrete measures are still lacking

At first glance, it seems that the role of agriculture, forests, and land use in mitigating and adapting to climate change is reflected in many NDCs, and that countries are committed to sustainable development in the sector. Some countries even set quantitative targets, such as Canada committing to reduce emissions from fertilizers by 30 per cent by 2030 and Ethiopia laying out conditional (i.e. dependent on international climate finance) and unconditional emissions reduction scenarios for the livestock and land use sectors.

Most countries provide concrete examples on how they plan to address the transitions needed to protect and restore nature and to develop a productive and regenerative agriculture. For example, the expansion of agroforestry systems is mentioned by Brazil (in the context of crop-livestock-forestry integration), Mexico, Colombia (aiming to integrate it in coffee and cocoa cultivation) and Ethiopia. Climate-smart agricultural practices are also often mentioned in the context of climate adaptation, including for example the adoption of cover cropping mentioned by Canada and the USA. The restoration of natural ecosystems, forests, degraded lands and soils is also mentioned by many NDCs, underlying the importance given to biodiversity conservation.

However, a deeper analysis revealed that countries still do not provide information on how these commitments will be implemented.

What’s next? The need for more ambitious and operational NDCs

While most analysed NDCs address food and land use systems, much work remains to be done if they are to drive meaningful action at the national level. Countries have left COP26 with the promise to “revisit and strengthen” their climate pledges by the end of 2022. This will be a chance to address the lack of focus on concrete priorities and policy measures, as well as the required financial and human resources, monitoring and evaluation processes, and coordination and institutional arrangements. In doing so, countries must focus on a few key areas.

Align national and subnational action with more ambitious NDCs

Ultimately, NDCs need to provide clear directions for the development of domestic policies, in line with international commitments and implemented across sectors.

Information on funding is particularly hard to come by with only Brazil and Canada referencing specific programmes and figures, respectively in the Low Carbon Agricultural Plan and the Agricultural Climate Solutions and Agricultural Clean Technology Programmes. Sectoral policies, on the other hand, are mentioned by about half of the NDCs, but only four included policies for both the agriculture and the land use sector.

But there are examples of countries that offer clear direction, such as the NDCs of Colombia and Ethiopia. Colombia describes several sectoral and territorial climate change plans to drive action at the national and subnational level. Ethiopia describes national policies and plans that support its pledges especially in the agriculture and land use sectors.

Adopt a holistic approach to food systems

The components of the food systems outside of food production are rarely taken into account, and several key transitions are not addressed in the NDCs. For instance, the United Kingdom is the only country to mention food storage and distribution in its pledge to phase down the use of HFC gases (i.e. freons or hydrofluorocarbons). Together with Colombia, it is also the only country to commit to a shift to healthy diets underpinned by a sustainable food system. On the other hand, Ethiopia is the only country to address the diversification of protein supply, including a commitment to a shift in demand from beef to chicken.

Worker harvesting bananas in the fields at Tandalwadi village in Jalgoan. Photo credit: Food and Land Use Coalition

Engage in policy dialogues across ministries and sectors

National policy is often developed and implemented in siloes, while implementing climate commitments requires coordinated action across all levels of government and across a range of stakeholders, including producers, consumers, the private sector, land managers, and Indigenous and local communities.

Most of the analysed NDCs do refer to the presence of inter-sectoral, inter-ministerial or broader advisory committees but it is difficult to assess their role or the extent to which these institutional arrangements are operational. Such processes and institutions should be made central in the development of climate policies and commitments.

The road to meeting the Paris Agreement is still very long, but COP26 provided a spark for the transformation of food and land use systems. Countries will need to seize this momentum to provide more ambitious and operational plans, and many have already started to do so. Learning from the blueprint and the positive examples set by other countries will be key in achieving this objective.