Dave Hale, Director of TechnoServe Labs, TechnoServe, outlines how technology can be used to make farming more inclusive, through three critical factors: setting targets, working with local partners and keeping the end-user in mind.

Drones are transforming how farmers go about their work. The agricultural drone market is already a $1.2 billion industry, as drones are helping farmers identify – down to the leaf – how their crops are doing and what steps are needed to improve their yields and reduce their production costs.

But while drones are now commonly seen flying above row crops in North America and Europe, and are starting to find use on large commercial farms in developing countries, they have not yet reached smallholder cocoa, coffee or cashew farmers in regions like sub-Saharan Africa.

We see that pattern often with new technology. As much as we talk about harnessing technology for development, new innovations are too often slow to reach those who need them most critically. How do we make technology more inclusive and enable it to reach traditionally excluded populations? Based on our experience in the field, including the launch of our new innovation hub, TechnoServe Labs, we have identified three critical factors.

- Set targets for inclusivity and measure against them

Impact measurement is central to our work, and we know that the metrics you choose are important: when you set targets at the beginning of an initiative, you design the project to achieve them. That is why it is so important to set targets that push you towards greater inclusivity.

At TechnoServe, for example, we have established an institutional goal that women make up at least 40 per cent of the farmers, entrepreneurs, and workers that our work supports. So when we partnered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to launch a project to work with cashew farmers in Benin, we set the same 40 per cent target. However, identifying and recruiting female cashew farmers for training was a challenge, as cooperatives and other existing channels were dominated by men. As we thought about how to support the project through the use of technology, we wanted to deploy tools that would help us reach our gender targets, rather than reinforce existing inequalities.

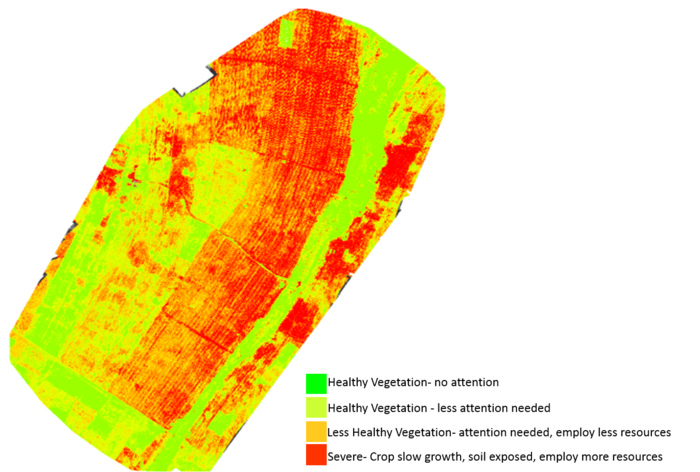

Perhaps surprisingly, drones and satellites can help in that process. As the result of a new partnership with Belgian Development Cooperation, data captured via remote sensing technology, including drones deployed over the countryside of Benin, will allow us to see and accurately identify the location of Benin’s cashew farms and what their agronomy needs are. So instead of relying on government offices or cooperative membership lists, and perhaps biased information about which farms need training, aerial imagery can identify farmers and the condition of their farms to target training services. We hope that unbiased data will help address structural gender imbalances in targeted training programs for 10,000 farmers in Benin.

IOM Uganda – Geospatial – An example of the kind of mapping that can be done with remote sensing technology.

- Work with local partners and the local ecosystem

It is also important to leverage, and build, local capacity. It is essential to work with organizations with on-the-ground experience and an understanding of the needs and capabilities of your target populations. Partnering with local research institutions, vocational training organizations, government agencies, and private-sector companies is also a good way to ensure that innovations fit within the local ecosystem and can be sustained after the end of a project.

Fortunately, technological innovation is not confined to Silicon Valley these days. Emerging tech hubs across Africa, Latin America, and Asia are bringing innovation closer to smallholder farmers and creating a number of new opportunities for partnership. In Benin, for example, we are partnering with local partners such as the Geographic Institute of Benin (IGNB) and Benin Flying Labs, a local robotics hub.

- Engage end users – starting with the design phase

Some of the biggest failures in incorporating technology in development contexts result from implementing solutions that do not fit the needs and capabilities of the target users. That is why there has been an increasing emphasis on engagement of local communities in testing, piloting, and rolling out new technological solutions.

To really ensure that technology is appropriate, however, it is important to go a step further: engagement with end-users and local communities should start in the design phase. Because technology designers and smallholder farmers do not always approach problems the same way, it’s important to build bridges between these groups so that they speak the same language. The MIT D-Lab is doing exciting work on this front. The D-Lab Creative Capacity Building methodology is human-centred design with strong community engagement – bringing local community members into the design process, and providing them with tools that they can use to develop their own solutions to their own problems.

By pulling together these approaches, we can help to ensure that technology reaches those who need it. A number of technologies, such as remote sensing (e.g. drones, satellite imagery, etc) and distance learning, amongst others, have the potential to create transformative change for smallholder farmers and others at the base of the pyramid and in vulnerable populations. By implementing a few best practices, we can ensure that this potential is realised.